NJSLA. An acronym that strikes fear into every student’s heart. It stands for “New Jersey Student Learning Assessments.” In short, it’s a state-required standardized test. One that proves to become more useless with every passing year.

In a perfect world, the NJSLA would be a way to assess students’ learning levels, testing how proficient they are in math and language arts (and for eighth graders, science). However, with quarantine, two years of testing were missed, and scores for the next one dropped significantly. However, the grading system itself could also be argued to be faulty. A student can score anywhere from a one to a five, with one being the worst and five being the best. The students are graded not by how well they did on the test, but by how well they did in comparison to other students.

Of course, this causes problems. A student who got every single answer wrong would typically get a low score on a normal test. On the NJSLA, they’re not only graded against the students that get all their answers correct, but also against the students that turn in a blank test because it doesn’t affect their grades, so in their eyes, it doesn’t matter. Therefore, the student with wrong answers would scrape out a better score than they typically would.

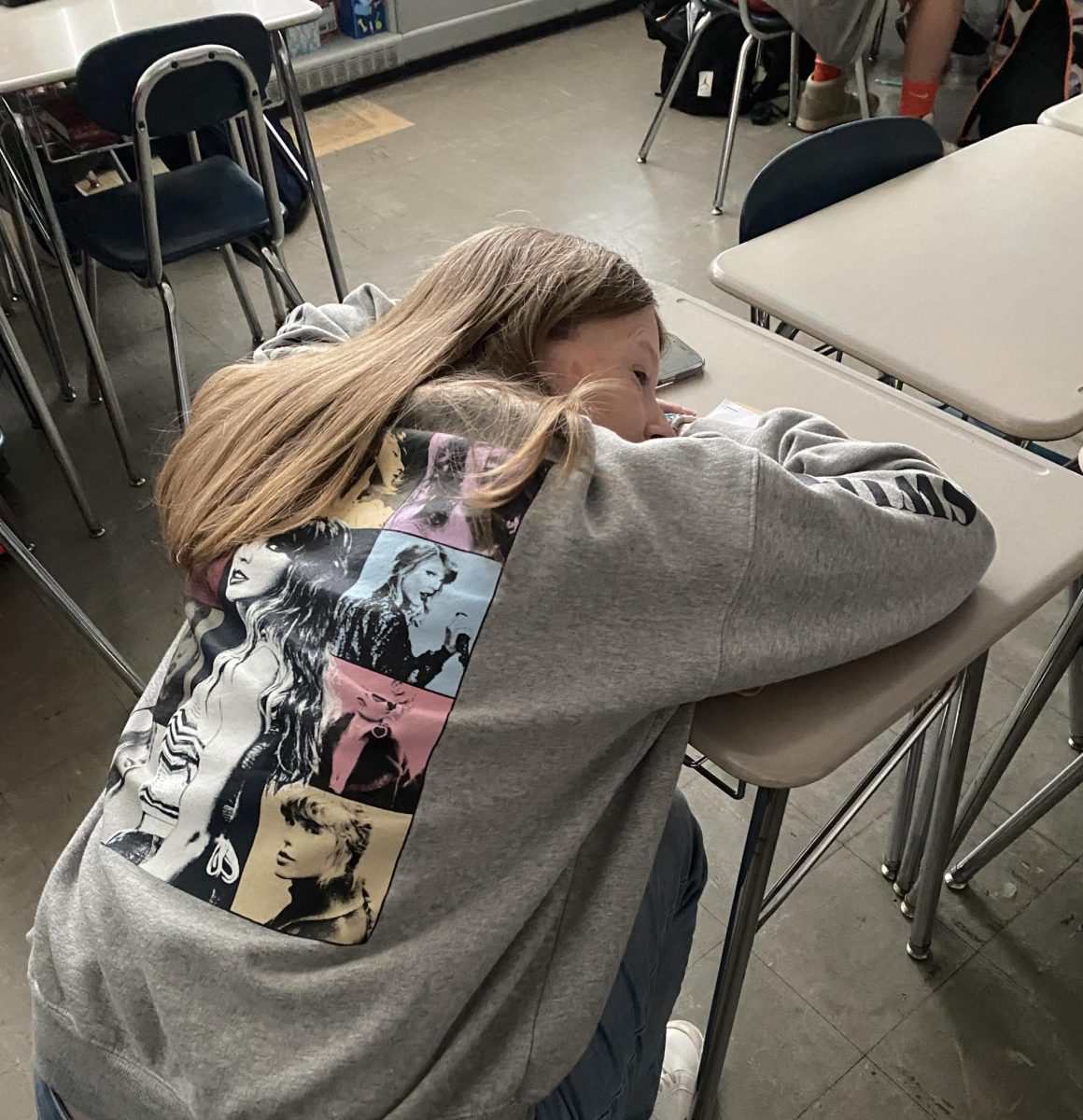

“If it were up to me, I wouldn’t make everyone take the test because it doesn’t do much. In all the time I’ve taken it, it hasn’t affected me.” remarks sixth grader Andersen Isolda. He shares his opinion with many of the other students at Edison. Plenty of students each year choose to not try or turn in blank tests because they don’t see the point in working hard on something that doesn’t affect them or their grades. “Improving scores for the school district” just isn’t a big enough motivator for kids to actually try to do well on the tests. And why should it be, when the tests almost feel as if they were designed to make the students fail?

“Testing puts a lot of pressure on us and there’s not enough time,” says seventh grader Meghan Riley. “Every student is different and we don’t all work at the same pace.” Meghan brings up a solid point. Every student is different, so shouldn’t the tests be, too? The district tries to solve this issue by creating different tests for different math levels, but they undermine it by differing every test. Some students will get a test that is completely different from others. While the tests could still be argued to be “the same level”, that completely destroys the intended concept of the “standardized test”. For another example, most students are in Science 8, a science class designed for eighth grade. However, one class in eighth grade takes Biology as part of the Gifted & Talented program. Evidently, the difference in classes never reached the ears of the creators of the NJSLA tests, because all eighth graders are made to take the test designed for Science 8. All of them. The Biology students were thrown into a test that they knew nothing about, and still expected to excel.

The real problem of the NJSLA test isn’t the test itself. The problem is that the NJSLA is supposed to be a standardized test, but it isn’t standardized. The definition of “standardized test” is a method of assessment built on the principle of consistency: all test takers on the same testing level are required to answer the same questions and all answers are graded in the same, predetermined way. Students on the same level should all have the same test. Furthermore, students should also be tested with their level, instead of with their grade. Age shouldn’t matter, only ability.

Furthermore, the tests take place over the course of a week and a half, with the majority of the day being taken up by the tests and the rest devoted to regular classes, which shrink to only 25 minutes each. “I think we should take two tests a day so it’s shorter. I think the tests are prolonged for no reason.” States English and Journalism teacher Mrs. Meade. With the tests being given so much time out of the day, that leaves very little for actual learning. 25 minutes isn’t nearly enough to teach a whole lesson. And since the tests go on for several days, this eliminates so much potential learning time for the students.

“The NJSLA was stressful, but I liked not having some of my classes,” admits eighth grader Ivonne Collazo-Marchany. If the tests are so useless to the students that the only thing they look forward to about the tests is the fact that they get to miss a few classes, the test doesn’t serve its purpose. While tests can be a drag for students, an effective standardized test would help them realize that they need to do well on the test to reflect well on their district. So while they might not be eager about taking it, they would hold more meaning in it than just skipping class.

The NJSLA tests are heavily flawed, and no better person to describe the flaws than a student. In the future, the tests should be designed with students of different abilities and ages in mind, and with more thought to how long they are and how much time they will take out of the day. There’s so much that could be improved upon, and almost none of it is taken into account. Students have so much untapped potential to help improve their own tests, and by extension, their test scores. When the tests almost seem designed to make the students do worse,the state shouldn’t be surprised when the tests they designed deliver bad scores.

Anon • Jan 22, 2024 at 8:56 pm

I was reading through this article and, while I’m aware this is a middle school level publication, the logic from the author is completely flawed. You state that the tests “almost feel as if they were designed to make the student fail”, but the lack of motivation to take the test from students doesn’t support this at all. Testing indeed puts a lot of pressure on students, but this is something that they need to get used to. And you state that the tests should be different because students are different but you also criticize the NJSLA tests for not being standardized? That just doesn’t follow. The tests are standardized for each subject so that each kid in a particular class will test on their subject along with their fellow peers. Biology in this case is an exception because 8th grade biology is a rarely offered course and the Science 8 test isn’t particularly hard. It’s intriguing to me that you think students should be tested with their own level because this is completely baseless. NJSLA tests are designed to standardize and get a baseline on the students in a particular grade; they are standardized for the reason of leveling all students in X grade because they should all be on the same level. The standardization of this test levels out each student so they can see where they rank in terms of readiness for high school and beyond. Although some students may be more gifted, the truth of it is that 8th grade students will get into college a year before 7th graders, and they must be tested differently to ensure their readiness for it. You also point to student laziness as a reason why NJSLA tests are ineffective. Students are going to be lazy regardless of how important the tests are. Again, you argue that the tests should hold more meaning even though you argued earlier to remove them entirely. And again, the entire testing situation should not bear down on students because the entire experience is to get the student used to stress or overly long tests. That is something all students need to learn and NJSLA tests teach that in addition to being an important benchmark for learning in our country.

Madeline • Feb 14, 2024 at 12:56 pm

Hi! I’m the author of this article. I was in eighth grade at the time, and a lot of my writing was definitely just my complaints about having to take the test and my issues with it. Your comment provided insight that I hadn’t thought of. Thanks for making me see a new point of view!